A miser tried to hide his gold but a thief saw where and took the gold. Too bad.

Wealth not used is wealth that does not exist.

Aesop For Children (The Miser)

A Miser had buried his gold in a secret place in his garden. Every day he went to the spot, dug up the treasure and counted it piece by piece to make sure it was all there. He made so many trips that a Thief, who had been observing him, guessed what it was the Miser had hidden, and one night quietly dug up the treasure and made off with it.

When the Miser discovered his loss, he was overcome with grief and despair. He groaned and cried and tore his hair.

A passerby heard his cries and asked what had happened.

“My gold! O my gold!” cried the Miser, wildly, “someone has robbed me!”

“Your gold! There in that hole? Why did you put it there? Why did you not keep it in the house where you could easily get it when you had to buy things?”

“Buy!” screamed the Miser angrily. “Why, I never touched the gold. I couldn’t think of spending any of it.”

The stranger picked up a large stone and threw it into the hole.

“If that is the case,” he said, “cover up that stone. It is worth just as much to you as the treasure you lost!”

Moral

A possession is worth no more than the use we make of it.

Samuel Croxall (The Covetous Man)

A POOR covetous wretch, who had scraped together a good parcel of money, went and dug a hole in one of his fields, and hid it. The great pleasure of his life was to go and look upon this treasure once a day, at least; which one of his servants observing, and guessing there was something more than ordinary in the place, came at night, found it, and carried it off. The next day, returning as usual to the scene of his delight, and perceiving it had been ravished away from him, he tore his hair for grief, and uttered the doleful complaints of his despair to the woods and meadows. At last, a neighbour of his, who knew his temper, overhearing him, and being informed of the occasion of his sorrow, Chear up, man! says he, thou hast lost nothing: there is the hole for thee to go and peep at still; and if thou canst but fancy thy money there, it will do just as well.

THE APPLICATION

Of all the appetites to which human nature is subject, none is so lasting, so strong, and at the same time so unaccountable as that of avarice. Our other desires generally cool and slacken at the approach of old age; but this flourishes under grey hairs, and triumphs amidst impotence and infirmhy. All our other longings have something to be said in excuse for them, let them be at what time of life soever. But it is above reason, and therefore truly incomprehensible, why a man should be passionately fond of money, only for the sake of gazing upon it. His treasure is as useless to him as a heap of oyster-shells; for though he knows how many substantial pleasures it is able to procure, yet he dares not touch it; and is as destitute of money, to all intents and purposes, as the man who is not worth a groat. This is the true state of a covetous person; to which one of the fraternity may possibly make this reply, that when we have said all, since pleasure is the grand aim of life, if there arises a delight to some particular persons from the bare possession of riches, though they do not, nor ever intend to make use of them, we may be puzzled how to account for it, and think it very strange, but ought not absolutely to condemn the men who thus closely, but innocently, pursue what they esteem the greatest happiness. True; people would be in the wrong to paint Covetousness in such odious colours, were it but compatible with innocence. But here arises the mischief, a truly covetous man will stick at nothing to attain his ends; and, when once avarice takes the field, Honesty, Charity, Humanity, and to be brief, every virtue which opposes it, is sure to be put to the rout.

Thomas Bewick (The Miser and His Treasure)

A certain Miser, having got together a large sum of money, sought out a sequestered spot, where he dug a hole and hid it. His greatest pleasure was to go and look upon his treasure; which one of his servants observing, and guessing there was something more than ordinary in the place, came at night, found the hoard, and carried it off. The next day, the Miser returning as usual to the scene of his delight, and perceiving the money gone, tore his hair for grief, and uttered the most doleful accents of despair. A neighbour, who knew his temper, overhearing him, said, Cheer up, man! thou hast lost nothing: there is still a hole to peep at: and if thou canst but fancy the money there, it will do just as well.

APPLICATION.

Of all the appetites to which human nature is subject, none is so lasting, so strong, and so unaccountable, as avarice. Other desires generally cool at the approach of old age; but this flourishes under grey hairs, and triumphs amidst infirmities. All our other longings have something to be said in excuse for them; but it is above reason, and therefore truly incomprehensible, why a man should be passionately fond of money only for the sake of gazing upon it. His treasure is as useless to him as a heap of oyster shells; for though he knows how many substantial pleasures it might procure, yet he dares not touch it, and is as destitute, to all intents and purposes, as the man who is not worth a groat. This is the true state of a covetous person, to which one of that fraternity perhaps may reply, that when we have said all, since pleasure is the grand aim of life, if there arise a delight to some, from the bare possession of riches, though they do not use, or even intend to use them, we may be puzzled how to account for it, and think it strange, but ought not absolutely to condemn those who thus closely, but innocently, pursue what they esteem the greatest happiness. True! people would be in the wrong to paint covetousness in such odious colours, were it compatible with innocence. But here arises the mischief: a covetous man will stop at nothing to attain his ends; and when once avarice takes the field, honesty, charity, humanity, and every virtue which opposes it, are sure to be put to the rout.

Eliot/Jacobs Version

There was a Miser who hid his gold at the foot of a tree in his garden. Every week he dug it up and gloated over his gains. A robber, who noticed this, dug up the gold and stole off with it. When the Miser next came to gloat over his treasures, he found nothing but the empty hole. He tore his hair, and raised such an outcry that all the neighbors came around him, and he told them how he used to come and visit his gold. “Did you ever take any of it out?” asked one of them. “No,” he said, “I only came to look at it.” “Then just look at the hole,” said a neighbor; “it will do you just as much good.”

JBR Collection (The Covetous Man)

A Miser once buried all his money in the earth, at the foot of a tree, and went every day to feast upon the sight of his treasure. A thievish fellow, who had watched him at this occupation, came one night and carried off the gold. The next day the Miser, finding his treasure gone, tore his clothes and filled the air with his lamentations. One of his neighbours told him that if he viewed the matter aright he had lost nothing. “Go every clay,” said he, “and fancy your money is there, and you will be as well off as ever.”

Townsend version (The Miser)

A miser sold all that he had and bought a lump of gold, which he buried in a hole in the ground by the side of an old wall and went to look at daily. One of his workmen observed his frequent visits to the spot and decided to watch his movements. He soon discovered the secret of the hidden treasure, and digging down, came to the lump of gold, and stole it. The Miser, on his next visit, found the hole empty and began to tear his hair and to make loud lamentations. A neighbor, seeing him overcome with grief and learning the cause, said, “Pray do not grieve so; but go and take a stone, and place it in the hole, and fancy that the gold is still lying there. It will do you quite the same service; for when the gold was there, you had it not, as you did not make the slightest use of it.”

L’Estrange version (A Miller Burying His Gold)

A certain covetous, rich churle sold his whole estate, and put it into mony, and then melted down that mony again into one mass, which he bury’d in the ground, with his very heart and soul in the pot for company. He gave it a visit every morning, which it seems was taken notice of, and somebody that observ’d him, found out his hoard one night, and carry’d it away. The next day he missed it, and ran allmost out of his wits for the loss of his gold. Well, (says a neighbour to him) and what’s all this rage for? Why you had no gold at all, and so you lost none. You did but fancy all this while that you had it, and you may e’en as well fancy again that you have it still. ‘Tis but laying a stone where you layd your mony, and fancying that stone to be your treasure, and there’s your gold again. You did not use it when you had it; and you do not want it so long as you resolve not to use it.

Moral

Better no estate at all, then the cares and vexations that attend the possession of it, without the use on’t.

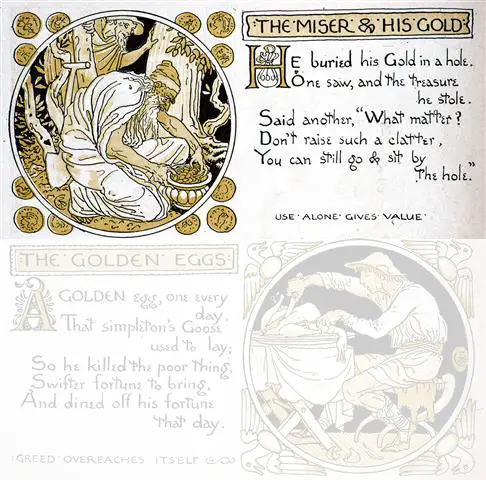

Crane Poetry Visual

He buried his Gold in a hole.

One saw, and the treasure he stole.

Said another, “What matter?

Don’t raise such a clatter,

You can still go & sit by the hole.”

Use alone gives value.

Gherardo Image from 1480

Avarus et Fur

Avarus quidam, suis omnibus bonis divenditis, auri massam emit eamque iuxta domus parietem profunda in fovea depositam summa cura servabat, accedensque continuo revisebat. Operarius autem quidam, qui eodem in loco versabatur, cum ipsum eo frequenter ire atque redire animadvertisset, statim quid rei esset intellexit. Olim itaque, postquam inde avarus discessit, eam auri massam subripuit. Reversus ille ac locum vacuum conspicatus, flere protinus atque capillos sibi vellere coepit. Quem ita se discruciantem cum quidam vidisset, ubi rei causam agnovit, “Ne doleas,” inquit, “sed lapidem cape, eodem in loco reconde et aurum ibidem esse finge tibi; auro enim, nec tum cum aderat, utebaris.”

Perry #225