[Read more…] about Mercury and The CarpenterA workman lost an axe. Mercury recovered a gold and silver axe which the workman refused. Mercury then recovered the real axe and gave him the others.

Truth is the better strategy.

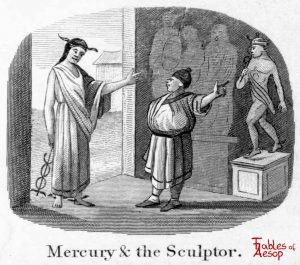

Mercury and The Sculptor

Townsend version

Mercury once determined to learn in what esteem he was held among mortals. For this purpose he assumed the character of a man and visited in this disguise a Sculptor’s studio having looked at various statues, he demanded the price of two figures of Jupiter and Juno. When the sum at which they were valued was named, he pointed to a figure of himself, saying to the Sculptor, “You will certainly want much more for this, as it is the statue of the Messenger of the Gods, and author of all your gain.” The Sculptor replied, “Well, if you will buy these, I’ll fling you that into the bargain.”

JBR Collection

Mercury, having a mind to know how much he was esteemed among men, disguised himself, and going into a Carver’s shop, where little images were sold, saw those of Jupiter, Juno, himself, and most of the other gods and goddesses. Pretending that he wanted to buy, he said to the Carver, pointing to the figure of Jupiter, “What do you ask for that?” “A shilling,” answered the Man. “And what for that?” meaning Juno. “Ah,” said the man, “I must have something more for that–eighteen pence, let us say.” “Well, and what, again, is the price of this?” said Mercury, laying his hand on a figure of himself, with wings, rod, and all complete. “Why,” replied the man, “if you really mean business, and will buy the other two, I’ll throw you that fellow in to the bargain.”

Samuel Croxall (Mercury and the Carver)

MERCURY having a mind to know how much he was esteemed among men, transformed himself into the shape of one of them; and going into a carver’s shop, where little images were to be sold, he saw Jupiter, Juno, himself, and most of the other gods and goddesses. So, pretending that he wanted to buy, says he to the carver, What do you ask for this? and pointed to the figure of Jupiter. A groat says the other. And what for that? meaning Juno. I must have something more for that, says he. Well, and What’s the price of this? says Mercury, nodding his head at himself. Why, says the man, if you are in earnest, and will buy the other two, I will throw you that into the bargain.

THE APPLICATION

Nothing makes a man so cheap and little in the eyes of discerning people, as his enquiring after his own worth, and wanting to know what value others set upon him. He that often busies himself in stating the account of his own merit, will probably employ his thoughts upon a very barren subject: those who are full of themselves, being generally the emptiest fellows. Some are so vain as to hunt for praise, and lay traps for commendation; which when they do, it is pity but they should meet with the same disappointment as Mercury in the fable. He that behaves himself as he should do, need not fear procuring a good share of respect, or raising a fair, flourishing reputation. These are the inseparable attendants of those that do well, and in course follow the man that acquits himself handsomely. But then they should never be the end or motive of our pursuits: our principal aim should be the welfare and happiness of our country, our friends, and ourselves; and that should be directed by the rules of honour and virtue. As long as we do this, we need not be concerned what the world thinks of us: for a curiosity of that kind does but prevent what it most desires to obtain. Fame, in this respect, is like a whimsical mistress: she flies from those who pursue her most, and follows such as show the least regard to her.

Thomas Bewick (Mercury and The Carver)

Mercury being very desirous to know what credit he had obtained in the world, and how he was esteemed among mankind, disguised himself, and went to the shop of a famous Statuary, where images were to be sold. He saw Jupiter, Juno, and himself, and most of the other gods and goddesses: so, pretending that he wanted to buy, he asked the prices of several, and at length pointing to Jupiter, What, says he, is the lowest price you will take for that? A crown, says the other; and what for that? pointing to Juno: I must have something more for that. Mercury then, casting his eye upon the figure of himself, with all his symbols about it, Here am I, said he to himself, in quality of Jupiter’s messenger, and the patron of artisans, with all my trades about me; and then smiling with a self-sufficient air, and pointing to the image, and pray friend, what is the price of this elegant figure? Oh, replied the Statuary, if you will buy Jupiter and Juno, I will throw you that into the bargain.

APPLICATION.

If we knew ourselves, of what could any of us be vain? Vanity is the fruit of ignorance, and the froth of perverted pride. Humility is the constant attendant on men of great talents and good qualities: these enable them to see how far they arc short of perfection; but the vain and arrogant conceive they have attained its height. All vain men, who affect popularity, fancy other people have the same opinion of them that they have of themselves; but nothing makes them look so cheap and little in the eyes of discerning people as their enquiring (like Mercury in the Fable) after their own worth, and wanting to know what value others set upon them: and those who are so full of themselves, as to hunt for praise, and lay traps for commendation, will generally be disappointed, and be marked out as the emptiest of fellows; for it argues a littleness of mind to be too anxious and solicitous concerning our fame. He that behaves himself as he should do, need not fear procuring a good share of respect, and a fair reputation; but then these should not be the end or the motive of our pursuits: our principal aim should 1 be the welfare of our country, our friends, and ourselves, and should be directed by the rules of honour and virtue.

Jefferys Taylor

WE’VE often made the beasts and birds

To speak their minds, and utter words:

So sure ’twill make but little odds

To introduce the heathen gods;

And if the fable’s understood,

I think you’ll say the moral’s good;

But should you not approve the same,

Aesop, not I must bear the blame.

Mercury, wishing much to know

How he was liked by men below

Disguised himself in shape of man,

As well we know such beings can;

And to a sculptor’s shop descended,

Where statues of the gods were vended:

There Jupiter and Juno stood,

In bronze, in marble, and in wood;

Mars and Minerva richly drest,

And Mercury amongst the rest.

Then said he to the sculptor, “Sir,

Pray what’s the price of Jupiter?”

The sum was named without delay:

“And what dy’e ask for Juno, pray?”

“A trifle more,” the man replied;

“She’s more esteem’d than most beside:”

“And what for that upon the shelf?”

Said Mercury, nodding at himself.

“O!” said the man, “his worth is small;

I never charge for him at all;

But when the other gods are bought,

I always give him in for nought.”

You ask me what I think of you,—

You’re foolish and conceited too.

No persons thus for praise will seek

But those who are both vain and weak.

L’Estrange version

Mercury had a great mind once to learn what credit he had in the world, and he knew no better way, then to put on the shape of a man, and take occasion to discourse the matter, as by the by, with a statuary: so away he went to the house of a great master, where, among other curious figures, he saw several excellent pieces of the gods. The first he cheapen’d was a Jupiter, which would have come at a very easy rate. Well (says Mercury) and what’s the price of that Juno there? The carver set that a little higher. The next figure was a Mercury, with his rod and his wings, and all the ensigns of his commission. Why, this is as it should be, says he, to himself: for here am I in the quality of Jupiter’s messenger, and the patron of artizans, with all my trade about me: and now will this fellow ask me fifteen times as much for this as he did for t’other: and so he put it to him, what he valu’d that piece at: why truly, says the statuary, you seem to be a civil gentleman, give me but my price for the other two, and you shall e’en have that into the bargain.

Moral

This is to put the vanity of those men out of countenance, that by setting too high a value upon themselves, appear by so much the more despicable to others.

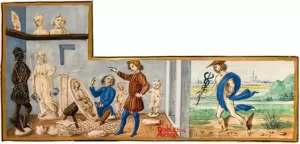

Gherardo Image from 1480

Mercurius et Statuarius

Mercurius, scire volens quanto in pretio apud homines esset, forma hominis induta, in statuarii officinam se contulit. In qua statuam Iovis conspicatus, eum, quanti ipsa veniret, interrogavit. Cui cum statuarius drachma dixisset, risit Mercurius et “Quanti,” inquit, “hoc Iunonis simulacrum?” Pluris illo dicente, Mercurius, sua quoque statua ibi visa, maximam de se ratus, utpote nuntio Deorum lucrique praeside, apud homines rationem haberi, quanti eam venderet ab artifice petiit. Tum statuarius “Si illas emeris,” inquit, “hanc tibi auctarium dabo.”

Moral

Hominem inanis gloriae studio captum fabula respicit, qui nullo in pretio est apud ceteros.

Perry #088

Jupiter’s Lottery

[Read more…] about Jupiter’s LotteryJupiter set up a lottery with Wisdom as prize. Minerva won but people were mad that Jupiter’s daughter won. Jupiter substituted Folly and people were happy.

The greatest fools have always looked upon themselves as the wisest men.

The Crow and Mercury

[Read more…] about The Crow and MercuryA Crow was caught but released by Apollo on promise of an offering. The offering was never made so when the Crow as again captured no other god helped.

Lie once and you may not be believed later.

Mercury and A Traveller

[Read more…] about Mercury and A TravellerA Traveler bargained safe passage with Mercury for half of any findings. He found nuts and dates and ate both leaving pits and shells for Mercury.

Peoples’ actions toward the gods differ from their words.

Mercury and Tiresias

[Read more…] about Mercury and TiresiasMercury wanted to test Tiresias; he stole some of Tiresias’ oxen and then went to him in human form. Tiresias predicted Mercury could help recover the oxen.

Vanity lives with fortune-tellers.