A Kite was bothering pigeons so the pigeons asked the hawk to guard them. Bad move as the hawk did more damage than the kite would have.

Avoid a remedy that is worse than the disease.

Townsend version

The pigeons, terrified by the appearance of a Kite, called upon the Hawk to defend them. He at once consented. When they had admitted him into the cote, they found that he made more havoc and slew a larger number of them in one day than the Kite could pounce upon in a whole year.

Moral

Avoid a remedy that is worse than the disease.

L’Estrange version

The pigeons finding themselves persecuted by the kite, made choice of the hawk for their guardian. The hawk sets up for their protector; but under countenance of that authority, makes more havock in the dove-house in two days, than the kite could have done in twice as many months.

Moral

‘Tis a dangerous thing for people to call in a powerful and an ambitious man for their protector; and upon the clamour of here and there a private person, to hazard the whole community.

[The following versions have the Kite as the king/guardian but with the same result.]

JBR Collection (The Kite and the Pigeons)

A Kite that had kept sailing around a dove-cote for many days to no purpose, was forced by hunger to have recourse to stratagem. Approaching the Pigeons in his gentlest manner, he tried to show them how much better their state would be if they had a king with some firmness about him, and how well his protection would shield them from the attacks of the Hawk and other enemies. The Pigeons, deluded by this show of reason, admitted him to the dove-cote as their king. They found, however, that he thought it part of his kingly prerogative to eat one of their number every day, and they soon repented of their credulity in having let him in.

Samuel Croxall (The Kite and the Pigeons)

A KITE, who had kept sailing in the air for many days near a dove-house, and made a stoop at several Pigeons, but all to no purpose, (for they were too nimble for him) at last had recourse to stratagem, and took his opportunity one day to make a declaration to them, in which he set forth his own just and good intentions, who had nothing more at heart than the defence and protection of the Pigeons in their ancient rights and liberties; and how concerned he was at their fears and jealousies of a foreign invasion, especially their unjust and unreasonable suspicions of himself, as if he intended, by force of arms, to break in upon their constitution, and erect a tyranical government over them. To prevent all which, and thoroughly to quiet their minds, he thought proper to propose to them such terms of alliance and articles of peace, as might for ever cement a good understanding betwixt them: the principal of which was, that they should accept of him for their king, and invest him, with all kingly privilege and prerogative over them. The poor simple Pigeons consented; the Kite took the coronation oath after a very solemn manner, on his part, and the Doves, the oaths of allegiance and fidelity, on theirs. But much time had not passed over their heads, before the good Kite pretended that it was part of his prerogative to devour a Pigeon whenever he pleased. And this he was not contented to do himself only, but instructed the rest of the royal family in the same kingly arts of government. The Pigeons, reduced to this miserable condition, said, one to the other, Ah! we deserve no better! Why did we let him come in?

THE APPLICATION

What can this fable be applied to, but the exceeding blindness and stupidity of that part of mankind, who wantonly and foolishly trust their native rights and liberty without good security? Who often chuse for guardians of their lives and fortunes, persons abandoned to the most unsociable vices; and seldom have any better excuse for such an error in politics, than, that they were deceived in their expectation; or never thoroughly knew the manners of their king, till he had got them entirely in his power. Which, however, is notoriously false; for many, with the Doves in the fable, are so silly, that they would admit of a Kite, rather than be without a king. The truth is, we ought not to incur the possibility of being deceived in so important a matter as this; an unlimited power should not be trusted in the hands of any one, who is not endued with a perfection more than human.

Thomas Bewick (The Kite and The Pigeons)

A Kite who had kept sailing in the air for many days near a dove-house, and made a stoop at several Pigeons to no purpose, for they were too nimble for him, at last had recourse to stratagem, and made a declaration to them, in which he set forth his own just and good intentions, and that he had nothing more at heart than the defence and protection of the Pigeons in their ancient rights and liberties, and how concerned he was at their unjust and unreasonable suspicions of himself, as if he intended by force of arms to break in upon their constitution, and erect a tyrannical government over them. To prevent all which, and thoroughly to quiet their minds, he thought proper to propose such terms of alliance, as might for ever cement a good understanding between them; one of which was, that they should accept of him for their king, and invest him with all kingly privilege and prerogative over them; in return for which he promised them protection from all their enemies. The poor simple Pigeons consented: the Kite took the coronation oath, after a very solemn manner, on his part, and the Doves the oaths of allegiance and fidelity on theirs. But much time had not passed over their heads before the good Kite pretended that it was part of his prerogative to devour a Pigeon whenever he pleased; and this he was not contented to do himself only, but instructed the rest of the royal family in the same kingly arts. The Pigeons, reduced to this miserable condition, said one to the other, Ah! we deserve no better! Why did we let him come in?

APPLICATION.

What can this Fable be applied to, but the exceeding blindness and stupidity of that part of mankind, who wantonly and foolishly trust their native rights of liberty without good security? Who often chuse for guardians of their lives and fortunes, persons abandoned to the most unsociable of vices; and seldom have any better excuse for such an error in politics, than that they were deceived in their expectation, or never thoroughly knew the manners of their king, till he had got them entirely in his power. We ought not to incur the possibility of being deceived in so important a matter as this; an unlimited power should not be trusted in the hands of any one who is not endowed with a perfection more than human.

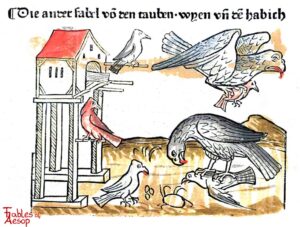

Heinrich Steinhöwel (Of the Doves, the Kite; and the Falcon)