A Boy about to be executed for stealing went to his Mother and bit her ear. He then accused her of abetting his first crime which later led to the gallows.

We are made by our teachings in youth.

Eliot/Jacobs Version

A Boy had been caught stealing and had been condemned to be executed. He desired to see his Mother and to speak with her before execution. When his Mother came to him he said: “I want to whisper to you,” and when she brought her ear near, he nearly bit it off. The bystanders were horrified, and asked him what he could mean by such brutal and inhuman conduct. “It is to punish her,” he said. “When I was young I began stealing little things and brought them home to Mother. Instead of punishing me, she laughed and said: “It will not be noticed.” It is because of her I am here today.”

Townsend version

A Boy stole a lesson-book from one of his schoolfellows and took it home to his Mother. She not only abstained from beating him, but encouraged him. He next time stole a cloak and brought it to her, and she again commended him. The Youth, advanced to adulthood, proceeded to steal things of still greater value. At last he was caught in the very act, and having his hands bound behind him, was led away to the place of public execution. His Mother followed in the crowd and violently beat her breast in sorrow, whereupon the young man said, “I wish to say something to my Mother in her ear.” She came close to him, and he quickly seized her ear with his teeth and bit it off. The Mother upbraided him as an unnatural child, whereon he replied, “Ah! if you had beaten me when I first stole and brought to you that lesson-book, I should not have come to this, nor have been thus led to a disgraceful death.”

Samuel Croxall

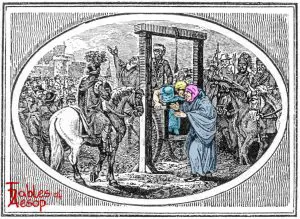

A LITTLE Boy, who went to school, stole one of his school-fellow’s horn-books, and brought it home to his mother; who was so far from correcting and discouraging him upon account of the theft, that she commended and gave him an apple for his pains. In process of time, as the child grew up to be a man, he accustomed himself to greater robberies; and at last, being apprehended and committed to gaol, he was tried and condemned for felony. On the day of his execution, as the officers were conducting him to the gallows, he was attended by a vast crowd of people, and among the rest by his mother, who came sighing and sobbing along, and taking on extremely for her son’s unhappy fate; which the criminal observing, called to the sheriff, and begged a favour of him, that he would give him leave to speak a word or two to his poor afflicted mother. The sheriff, as who would deny a dying Man so reasonable a request) [sic] gave him permission; and the felon, while as every one thought, he was whispering something of importance to his mother, bit off her ear, to the great offence and surprise of the whole assembly. What, say they, was not this villain contented with the impious facts that he has already committed, but that he must increase the number of them, by doing this violence to his mother? Good people, replied he, I would not have ye be under a mistake; that wicked woman deserves this, and even worse at my hands; for if she had chastised and chid, instead of rewarding and caressing me when in my infancy I stole the hornbook from the school, I had not come to this ignominious, untimely end.

THE APPLICATION

Notwithstanding the great innate depravity of mankind, one need not scruple to affirm, that most of the wickedness which is so frequent and so pernicious in the world, arises from a bad education; and that the child is obliged either to the example or connivance of its parents, for the most of the vicious habits which it wears through the course of its future life. The mind of one that is young is like wax, soft, and capable of any impression which is given it; but is hardened by time, and the first signature grows so firm and durable, that scarce any pains or applications can erase it. It is a mistaken notion in people, when they imagine that there is no occasion for regulating or restraining the actions of very young children, which, though allowed to be sometimes very naughty in those of a more advanced age, are in them, they suppose, altogether innocent and inoffensive. But, however innocent they may be, as to their intention then, yet, as the practice may grow upon them unobserved, and root itself into a habit, they ought to be checked and discountenanced in their first efforts towards any thing that is injurious or dishonest; that the love of virtue and the abhorrence of wrong and oppression, may be let into their minds, at the same time that they receive the very first dawn of understanding, and glimmering of reason. Whatever guilt arises from the actions of one whose education has been deficient as to this point, no question but a just share of it will be laid, by the Great Judge of the world, to the charge of those who were, or should have been his instructors.

JBR Collection

A little Boy, who went to school, stole one of his schoolfellow’s books and took it home. His Mother, so far from correcting him, took the book and sold it, and gave him an apple for his pains. In the course of time the Boy became a robber, and at last was tried for his life and condemned. He was led to the gallow’s, a great crowd of people following, and among them his Mother, bitterly weeping. He prayed the officers to grant him the favour of a few parting words with her, and his request was freely granted. He approached his Mother, put his arm round her neck, and making as though he would whisper something in her car, bit it off. Her cry of pain drew everybody’s eyes upon them, and great was the indignation that at such a time he should add another violence to his list of crimes. “Nay, good people,” said he, “do not be deceived. My first theft was of a book, which I gave to my Mother. Had she whipped me for it, instead of praising me, I should not have come to the gallows now that I am a man.”

Thomas Bewick

A little Boy having stolen a book from one of his school-fellows, took it to his Mother, who, instead of correcting him, praised his sharpness, and rewarded him. In process of time, as he grew bigger, he increased also in villainy, till at length he was taken up for committing a great robbery, and was brought to justice and condemned for it. As the officers were conducting him to the gallows, he was attended by a vast crowd, and among the rest his Mother came sobbing along, and deploring her son’s unhappy fate; which the criminal observing, he begged leave to speak to her: this being granted, he put his mouth to her ear, as if he was going to whisper something, and bit it off! The officer, shocked at this behaviour, asked him if the crimes he had committed were not sufficient to glut his wickedness, without being also guilty of such an unnatural violence towards his mother? Let no one wonder, said he, that I have done this to her, for she deserves even worse at my hands. For if she had chastised instead of praising and encouraging me, when I stole my school-fellow’s book, I should not now have been brought to this ignominious and untimely end.

APPLICATION.

The approaches to vice are by slow degrees, and the good or evil bias given to youth is seldom eradicated. The first deviations from sound morality should therefore be most strictly watched, and wickedness checked or punished in time; for when vice grows into a habit, it becomes incurable, and both good governments and private families are deeply concerned in its attendant consequences. One need not scruple to affirm that most of the depravity which is so frequent in the world, and so pernicious to society, is owing to the bad education of youth; and to the connivance or ill example of their parents. It is therefore of the utmost consequence that parents, guardians, and tutors, should be of characters befitting them for the various and important offices they have to perform. The latter description of persons may and ought to be carefully selected; but it is to be lamented that the base and mean-spirited hosts of bad parents are out of the reach of controul, [sic] and nothing can prevent the evils arising from their tutorage. Perhaps it would be harsh to make laws to check the marriages of such; but there is no need to encourage the breed of them, for they are already over abundantly numerous.

L’Estrange version

A school-boy brought his mother a book that he had stoll’n from one of his fellows. She was so far from correcting him for’t, that she rather encourag’d him. As he grew bigger, he would be still keeping his hand in use with somewhat of greater value, till he came at last to be taken in the matter, and brought to justice for’t. His mother went along with him to the place of execution, where he got leave of the officers, to have a word or two in private with her. He put his mouth to her ear, and under the pretext of a whisper, bit it clear off. This impious unnatural villany turn’d every bodies heart against him more and more. Well good people (says the boy) here you see me an example, both upon the matter of shame and of punishment; and it is this mother of mine that has brought me to’t; for if she had but whipt me soundly for the book I stole when I was a boy, I should never have come to the gallows here now I’m a man.

Moral

We are either made or marr’d, in our education; and governments, as well as private families, are concern’d in the consequences of it.

Gherardo Image from 1480

Fur et Mater Eius

Quidam puer in schola, libellum furatus, suae attulit matri. A qua non castigatus, quotidie furabatur magis atque magis; progressu autem temporis, maiora furari coepit. Tandem a magistratu deprehensus, ducebatur ad supplicium. Matre vero sequente ac vociferante, ille rogavit ut sibi liceret paulisper cum ea loqui ad aurem. Illo permisso et matre properante et aurem admovente ad filii os, dentibus suis matris auriculam evulsit. Cum mater et ceteri qui adstabant eum increparent, non modo ut furem, sed etiam ut impium in parentem suam, inquit, “Haec causa fuit exitii mei. Etenim si me castigasset prius ob libellum quem furatus sum, nil fecissem ulterius; nunc ducor ad supplicium.”

Perry #200