Belly had all the food and the rest of the body rebelled and refused to work to get more. They soon relented as the whole body started to starve.

The person who withdraws support for his leader is a traitor.

Eliot/Jacobs Version

One day it occurred to the Members of the Body that they were doing all the work while the Belly had all the food. So they held a meeting and decided to strike till the Belly consented to its proper share of the work. For a day or two, the Hands refused to take the food, the Mouth refused to receive it, and the Teeth had no work to do. After a day or two the Members began to find that they themselves were in poor condition: the Hands could hardly move, and the Mouth was parched and dry, while the Legs were unable to support the rest. Thus even the Belly was doing necessary work for the Body, and all must work together or the Body will go to pieces.

Samuel Croxall

IN former days, When the Belly and the other parts of the body enjoyed the faculty of speech, and had separate views and designs of their own; each part, it seems, in particular, for himself, and in the name of the whole, took exception at the conduct of the Belly, and were resolved to grant him supplies no longer. They said they thought it very hard, that he should lead an idle good-for-nothing life, spending and squandering away, upon his own ungodly guts, ail the fruits of their labour; and that, in short, they were resolved for the future to strike off his allowance, and let him shift for himself as well as he could. The hands protested they would not lift up a finger to keep him from starving; and the mouth wished he might never speak again, if he took in the least bit of nourishment for him so long as he lived; and, say the teeth, may we be rotten if ever we chew a morsel for him for the future. This solemn league and covenant was kept as long as any thing of that kind can be kept, which was, until each of the rebel members pined away to the skin and bone, and could hold ont no longer. Then they found there was no doing without the Belly, and that, as idle and insignificant as he seemed, he contributed as much to the maintenance and welfare of all the other parts, as they did to his.

THE APPLICATION

This fable was spoken by Menenius Agrippa, a famous Roman consul and genera), when he was deputed by the senate to appease a dangerous tumult and insurrection of the people. The many wars that nation was engaged in, and the frequent supplies they were obliged to raise, had so soured and inflamed the minds of the populace, that they were resolved to endure it no longer, and obstinately refused to pay the taxes which were levied upon them. It is easy to discern how the great man applied his fable. For, if the branches and members of a community refuse the government that aid which its necessities require, the whole must perish together. The rulers of a state, as idle and insignificant as they may sometimes seem, are yet as necessary to be kept up and maintained in a proper and decent grandeur, as the family of eat h private person is, in a condition suitable to itself. Every man’s enjoyment of that little which he gains by his daily labour, depends upon the government’s being maintained in a condition to defend and secure him in it.

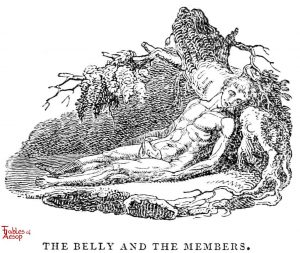

Thomas Bewick (The Belly and The Members)

In former days, it happened that the Members of the human body, taking some offence at the conduct of the Belly, resolved no longer to grant it the usual supplies. The Tongue first, in a seditious speech, aggravated their grievances; and after highly extolling the activity and diligence of the Hands and Feet, set forth how hard and unreasonable it was, that the fruits of their labour should be squandered away upon the insatiable cravings of a fat and indolent paunch. In short, it was resolved for the future to strike off his allowance, and let him shift for himself as well as he could. The Hands protested they would not lift a Finger to keep him from starving; and the Teeth refused to chew a single morsel more for his use. In this distress, the Belly remonstrated with them in vain; for during the clamour of passion the voice of reason is always disregarded. This unnatural resolution was kept as long as any thing of that kind can be kept, which was, until each of the rebel members pined away to the skin and bone, and could hold out no longer. Then they found there was no doing without the Belly, and, that idle and insatiable as it seemed, it contributed as much to the welfare of all the other parts, as they in their several stations did towards its maintenance.

APPLICATION.

This Fable was spoken by Menenius Agrippa, a Roman consul and general, when he was deputed by the senate to appease a dangerous tumult and insurrection of the people. The many wars the Romans were engaged in, and the frequent supplies they were obliged to raise, had so soured and inflamed the minds of the populace, that they were resolved to endure it no longer, and obstinately refused to pay the taxes. It is easy to discern how the great man applied this Fable: for, if the branches and members of a community refuse the government that aid which its necessities require, the whole must perish together. The rulers of a state, useless or frivolous as they may sometimes seem, are yet as necessary to be kept up and maintained in a proper and decent grandeur, as the family of each private person is, in a condition suitable to itself. Every man’s enjoyment of that little which he gains by his daily labour, depends upon the government’s being maintained in a condition to defend and secure him in the unmolested control and possession of it.

Townsend version

The members of the Body rebelled against the Belly, and said, “Why should we be perpetually engaged in administering to your wants, while you do nothing but take your rest, and enjoy yourself in luxury and self-indulgence?” The Members carried out their resolve and refused their assistance to the Belly. The whole Body quickly became debilitated, and the hands, feet, mouth, and eyes, when too late, repented of their folly.

Jefferys Taylor (The Mouth and The Limbs)

IN days of yore, they say, ’twas then

When all things spoke their mind;

The arms and legs of certain men

To treason felt inclined.

These arms and legs together met,

As snugly as they could,

With knees and elbows, hands and feet,

In discontented mood.

Said they, “‘Tis neither right nor fair,

Nor is there any need,

To labour with such toil and care,

The greedy mouth to feed.”

“This we’re resolv’d no more to do,

Though we so long have done it;”

“Ah!” said the knees and elbows too,

“And we are bent upon it.”

“I,” said the tongue, “may surely speak,

Since I his inmate am;

And for his vices while you seek,

His virtues I’ll proclaim.

“You say the mouth embezzles all

The fruit of your exertion;

But I on this assembly call

To prove the base assertion.

“The food which you with labour gain,

He too with labour chews;

Nor does he long the food retain,

But gives it for your use.

“But he his office has resign’d

To whom you may prefer;

He begs you therefore now to find

Some other treasurer.”

“Well, be it so,” they all replied;

“His wish shall be obey’d;

We think the hands may now be tried

As treasurers in his stead.”

The hands with joy to this agreed,

And all to them was paid;

But they the treasure kept indeed,

And no disbursements made.

Once more the clam’rous members met,

A lean and hungry throng;

When all allow’d from head to feet,

That what they’d done was wrong.

To take his office once again,

The mouth they all implored;

Who soon accepted it, and then

Health was again restored.

This tale for state affairs is meant,

Which we need not discuss;

At present we will be content,

To find a moral thus:—

The mouth has claims of large amount

From arms, legs, feet, and hands;

But let them not, on that account,

Pay more than it demands.

JBR Collection

The members of the Body once rebelled against the Belly, who, they said, led an idle, lazy life at their expense. The Hands declared that they would not again lift a crust even to keep him from starving, the Mouth that it would not take in a bit more food, the Legs that they would carry him about no longer, and so on with the others. The Belly quietly allowed them to follow their own courses, well knowing that they would all soon come to their senses, as indeed they did, when, for want of the blood and nourishment supplied from the stomach, they found themselves fast becoming mere skin and bone.

L’Estrange version

The commoners of Rome were gon off once into a direct faction against the Senate. They’d pay no taxes, nor be forc’d to bear arms, they said, and ’twas against the liberty of the subject to pretend to compel them to’t. The sedition, in short, ran so high, that there was no hope of reclaiming them, till Menenius Agrippa brought them to their wits again by this apologue: The hands and the feet were in a desperate mutiny once against the belly. They knew no reason, they said, why the one should lye lazying, and pampering it self with the fruit of the others labour; and if the body would not work for company, they’d be no longer at the charge of maintaining it. Upon this mutiny, they kept the body so long without nourishment, that all the parts suffer’d for’t: insomuch that the hands and feet came in the conclusion to find their mistake, and would have been willing then to have done their office; but it was now too late, for the body was so pin’d with over-fasting, that it was wholly out of condition to receive the benefit of a relief: which gave them to understand, that body and members are to live and die together.

Moral

The publick is but one body, and the prince the head on’t; so that what member soever withdraws his service from the head, is no better than a negative traitor to his country.

Membra et Venter

Membra quondam dicebant ventri, “Nosne te semper ministerio nostro alemus, dum tu summo otio frueris? Hoc non diutius faciemus.” Dum igitur ventri cibum subducunt, corpus debilitatum est, et membra sero invidiae suae paenituit.

Perry #130