A Schoolmaster found his Scholar hanging to a branch in the river. Scholar had tried to swim unaided before he could. The Master helped teach the lesson.

Know your abilities before attempting a task.

JBR Collection

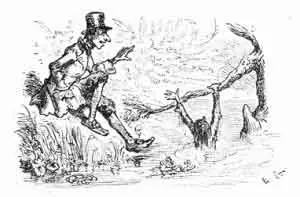

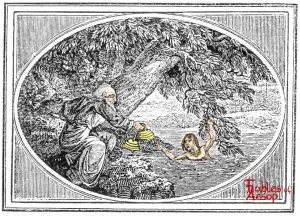

As a Schoolmaster was walking upon the bank of a river, not far from his School, he heard a cry, as of some one in distress. Running to the side of the river, he saw one of his Scholars in the water, hanging by the bough of a willow. The Boy, it seems, had been learning to swim with corks, and fancying that he could now do without them, had thrown them aside. The force of the stream hurried him out of his depth, and he would certainly have been drowned, had not the friendly branch of a willow hung in his way. The Master took up the corks, which were lying upon the bank, and threw them to his Scholar. “Let this be a warning to you,” said he, “and in your future life never throw away your corks until you are quite sure you have strength and experience enough to swim without them.”

Samuel Croxall

AS a Schoolmaster was walking upon the bank of a river, not far from his school, he heard a cry as of one in distress; advancing a few paces farther, he saw one of his Scholars in the water, hanging by the bough of a willow. The boy had, it seems, been learning to swim with corks: and now, thinking himself sufficiently experienced, had thrown those implements aside, and ventured into the water without them; but the force of the stream having hurried him out of his depth, he had certainly been drowned, had not the branch of a willow, which grew on the bank, providentially hung in his way. The Master took up the corks, which lay upon the ground, and throwing them to his Scholar, made use of this opportunity to read a lecture to him upon the inconsiderate rashness of youth. Let this be an example to you, says he, in the conduct of your future life, never to throw away your corks till time has given you strength and experience enough to swim without them.

THE APPLICATION

Some people are so vain and self-conceited, that they will run themselves into a thousand inconveniences, rather than be thought to want assistance in any one respect. Now there are many little helps and accommodations in life, which they who launch out into the wide ocean of the world ought to make use of as supporters to raise and buoy them up, till they are grown strong in the knowledge of men, and sufficiently versed in business, to stem the tide by themselves. Yet many, like the child in the fable, through an affectation of being thought able and experienced, undertake affairs which are too big for them, and venture out of their depth, before they find their own weakness and inability.

Few are above being advised: nor are we ever too old to learn any thing which we may be the better for. But young men, above all, should not distain to open their eyes to example, and their ears to admonition. They should not be ashamed to furnish themselves with rules for their behaviour in the world. However mean it may seem to use such helps, yet it is really dangerous to be without them. As a man who is lame with the gout, had better draw the observations of people upon him, by walking with a crutch, than expose himself to their ridicule by tumbling down in the dirt. It is as unnatural to see a young man throw himself out in conversation with an assuming air, upon a subject which lie knows nothing of, as for a child of three months old to be left to go without its leading-strings; they are equally shocking and painful to the spectator. Let them have but patience till time and experience strengthen the mind of the one, and the limbs of the other, and they may both make such excursions as may not be disagreeable or offensive to the eye of the beholder.

And here it may not be improper to say something by way of application to the whole. It is not expected that they who are versed and hackneyed in the paths of life should trouble themselves to peruse these little loose sketches of morality; such may do well enough without them. They are written for the benefit of the young and the unexperienced; if they do but relish the contents of this book, so as to think it worth reading over two or three times, it will have attained its end; and should it meet with such a reception, the several authors originally concerned in these fables, and the present compiler of the whole, may be allowed not altogether to have misemployed their time, in preparing such a collation for their entertainment.

Thomas Bewick

As a School-master was walking upon the bank of a river, he heard a cry as of one in distress: advancing a few paces farther, he saw one of his Scholars in the water, hanging by the branch of a willow. The Boy had, it seems, been learning to swim with corks, and now thinking himself sufficiently experienced, had thrown these implements aside, and ventured into the water without them; but the force of the stream having harried him out of his depth, he had certainly been drowned, had not the branch of the tree providentially hung in his way. The Master took up the corks, which lay upon the ground, and throwing them to his Scholar, made use of this opportunity to read a lecture to him upon the inconsiderate rashness of youth. Let this be an example to you, says he, in the conduct of your future life, never to throw away your corks till time has given you strength and experience enough to swim without them.

APPLICATION.

Rashness is the peculiar vice of youth, and may be stiled the characteristic foible of that season of life. The foundation of this rashness is laid in a fond conceit of their own abilities, which tempts them to undertake affairs too great for their capacities, and to venture out of their depths, or to suffer themselves to be hurried into the most precipitate and dangerous measures, before they find out their own weakness and inability. It therefore behoves inexperienced young men to keep a cautious guard over their passions, to check the irregularities of their disposition, and to listen to the wholesome advice and good council of those whose judgments are matured by age and experience: for few are above the need of advice, nor are we ever too old to learn any thing for which we may be the better. But young men, above all, should not disdain to open their eyes to good example, and their ears to admonition: neither should they be ashamed to borrow rules for their behaviour in the world, until they are enabled from their own knowledge of men and things, to stem its crooked tides and currents with ease and honour to themselves.

Consult your elders, use their sense alone, Till age and practice have confirm'd your own.